[ad_1]

Kigali, Rwanda

The church at Ntarama, a 45-minute drive south of Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, is a red-brick constructing about 20 metres lengthy by 5 metres extensive. Inside are options seen in Catholic church buildings world wide: pews for congregation members, an altar, stained-glass home windows and a cross adorning the doorway. Then there are the scars of the unimaginable: piles of blood-stained clothes hanging alongside the partitions and glass cupboards containing greater than 260 human skulls, many fractured or shattered, some with rusted weapons nonetheless penetrating them. Close by, picket sticks and roughly carved golf equipment lean towards the altar.

Ntarama is the positioning of one of many many massacres that occurred throughout the 1994 genocide towards the Tutsi in Rwanda — one of many worst atrocities of the late twentieth century. Beginning on 7 April that 12 months, in 100 days of horrifying violence, members of the Hutu ethnic group systematically killed an estimated 800,000 Tutsi — or a couple of million, in accordance with the Rwandan authorities and different sources. The killers ranged from militias to peculiar residents, with neighbours turning on neighbours. Many reasonable Hutu and among the Twa minority group have been additionally killed.

Rwanda: From killing fields to technopolis

Greater than 5,000 Tutsi have been murdered at Ntarama, amongst them infants, youngsters and pregnant ladies, a lot of whom have been raped earlier than they have been killed, says Evode Ngombwa, web site supervisor on the Ntarama Genocide Memorial, one in all six websites in Rwanda that commemorate the atrocity. “Folks used cash to bribe the perpetrators in order that they may select the best way of being eradicated. As an alternative of killing them with machetes, they may select to be shot,” says Ngombwa as he walks me by way of the church. With extra stays being discovered every year, about 6,000 individuals at the moment are buried there in mass graves.

This month, Rwanda and the world start commemorations to mark 30 years because the begin of this atrocity. The genocide is now probably the most studied of its variety. Researchers from social and political scientists to mental-health specialists, geneticists and neuroscientists have investigated the occasion and its aftermath in a manner that hadn’t been doable for earlier atrocities.

This work is very essential now in gentle of violent crises in a number of elements of the world, together with in Ukraine, Israel and Gaza, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Though there may be debate about whether or not these conflicts meet the definition of genocide, some share comparable traits. Analysis carried out into atrocities such because the genocide in Rwanda will help to tell responses and longer-term approaches to therapeutic.

Regardless of the difficulties of those research, researchers say that they’re working in the direction of growing a concept of genocide and the situations that spur mass violence. They’re offering steering for first responders, in addition to these concerned in peacebuilding and supporting survivors of different systematic mass murders and of battle. A few of their approaches have been utilized in different conflicts. And the analysis on Rwanda is providing classes for a way students can enhance research of comparable occasions.

At a vigil in April 2019, younger Rwandans commemorate the twenty fifth anniversary of the genocide.Credit score: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty

“Genocide research are essential,” says Phil Clark, an international-politics researcher at SOAS, a part of the College of London, who has studied Rwanda for greater than twenty years. “If we will begin to perceive why and the way genocides occur, and particularly if we will evaluate genocides internationally, we should always ideally have the ability to construct a basic concept of how these horrible occasions are even doable.”

One of many classes rising from Rwanda is the significance of involving — and supporting — native researchers, whose work, language expertise and entry to traumatized communities could be important for understanding the roots of violence and the very best strategies for reconciliation. This may be troublesome — in Rwanda’s case as a result of the genocide worn out nearly its total educational neighborhood. Now, by way of programmes geared toward elevating native students’ voices, their work is lastly reaching a wider viewers.

Patterns of violence

Earlier than 1994, the sphere of genocide research was dominated by the Holocaust — the systematic killing of 6 million Jewish individuals by Nazi Germany throughout the Second World Battle. “It’s solely within the final 20 years that different genocides have entered the dialogue,” says Clark. However analysis on Rwanda didn’t begin instantly. “It was solely perhaps 10–15 years after the genocide that students began to essentially interrogate this query of what drove a whole lot of 1000’s of on a regular basis civilians to take part in mass violence.”

Students say that it’s essential to not overlook the genocide’s sturdy hyperlink to colonialism in Rwanda. Within the early 1900s, Belgian colonizers started formally dividing Rwandan individuals into social courses: Hutu, Tutsi and Twa. Designations have been typically primarily based on pseudoscientific concepts, together with phrenology and arbitrary observations, equivalent to what number of cattle an individual owned. Ethnic tensions between Hutu and Tutsi intensified over the many years and a number of other massacres of Tutsi occurred within the interval main as much as 1994. This set the stage for a descent into genocide — a authorized time period that’s outlined by the perpetration of sure crimes which are supposed to destroy a selected group, and is codified by the United Nations’ 1948 Genocide Conference.

Every genocide is exclusive, says Timothy Longman, a political scientist at Boston College in Massachusetts, who first went to Rwanda in 1992 and returned in 1995 as a researcher with Human Rights Watch, a global non-governmental group that was one of many first to research the occasion. “However there are also some widespread patterns,” he says. Researchers can be taught lots from learning circumstances equivalent to Rwanda, the Holocaust and different genocides, he says. “It lets you stop violence from taking place elsewhere.”

One of many foremost scientific contributions of research up to now are the insights from mental-health researchers, a lot of whom have been on the bottom within the instant aftermath. Over the previous three many years, they’ve documented the preliminary trauma of a complete nation and the sluggish restoration of survivors and their youngsters, a lot of whom are vulnerable to being retraumatized. With few accessible sources, Rwanda needed to construct up its mental-health providers and it has gained distinctive expertise in responding to the atrocity’s aftermath.

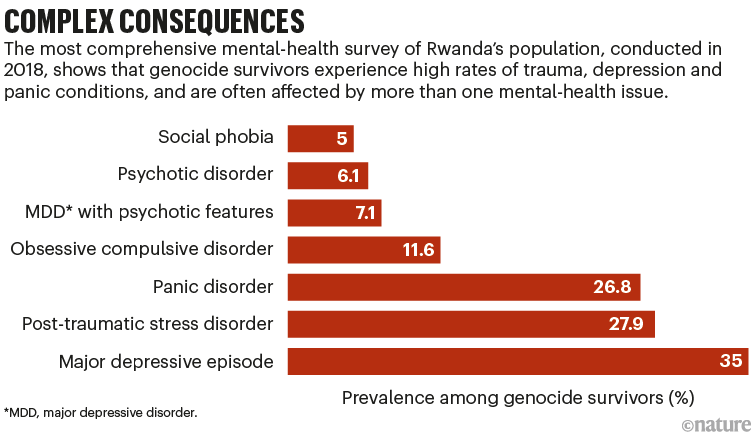

Supply: Y. Kayiteshonga et al. Rwanda Psychological Well being Survey 2018 (Govt of Rwanda, 2021).

On the Rwanda Biomedical Centre (RBC) in Kigali, the nation’s foremost well being group, Jean Damascène Iyamuremye remembers his expertise of 1994. “I witnessed all the things that occurred.” Iyamuremye was a 28-year-old coaching to be a medical assistant, however the genocide spurred him to concentrate on psychological well being. He was among the many first medical employees supporting survivors. “We have been like firefighters,” says Iyamuremye, who’s now director of the psychiatric unit within the RBC’s mental-health division, which oversees countrywide providers.

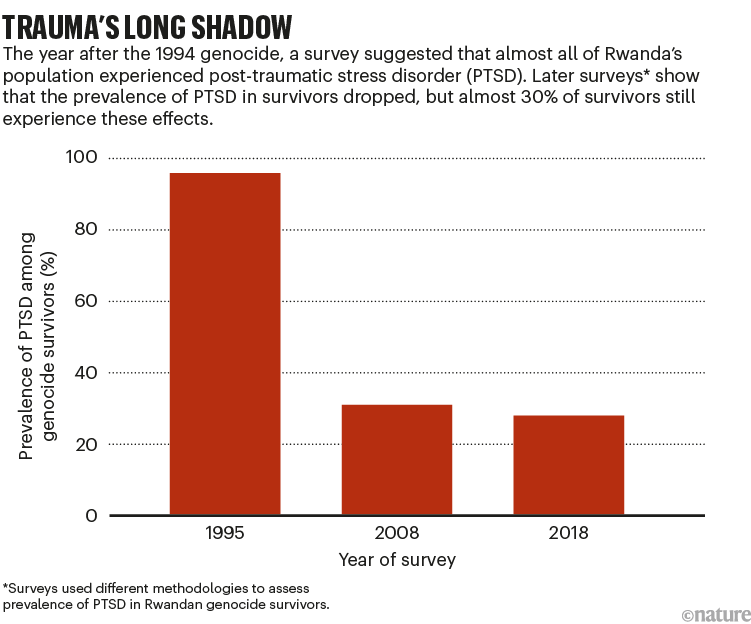

The primary care got here largely from outsiders. Non-governmental organizations offered psychological interventions equivalent to counselling for the survivors, most of whom had skilled bodily violence in addition to unimaginable emotional trauma from the mass killings they’d witnessed. After the genocide, 96% of Rwandans skilled post-traumatic stress dysfunction (PTSD) on account of the intense violence1.

It took time for the nation to develop its personal mental-health sources. In 1994, Rwanda had just one psychiatrist, Naasson Munyandamutsa, who was dwelling in Switzerland on the time and misplaced most of his household within the violence. Munyandamutsa returned rapidly to Rwanda to work on the nation’s sole psychiatric hospital, the place he started coaching mental-health responders and psychiatrists.

Whereas Munyandamutsa, who died in 2016, led the coaching of practitioners in Rwanda, many Rwandans went abroad to coach. However about half didn’t return, says Iyamuremye.

It wasn’t till 2014 that Rwanda had its personal college of psychiatry, on the College of Rwanda in Kigali. Even now, the nation has solely 16 psychiatrists, 13 of whom graduated from that facility, to serve a fast-growing inhabitants of 13.5 million.

Proof-based interventions for survivors, equivalent to counselling, cognitive behavioural remedy and drugs, have continued — however individuals nonetheless bear vital psychological scars from their experiences (see ‘Advanced penalties’). In Rwanda’s most complete mental-health survey but, carried out by the RBC in 2018, about 28% of genocide survivors reported PTSD signs, in contrast with 3.6% of the final inhabitants (see ‘Trauma’s lengthy shadow’).

Sources: Ref. 1; A. Eytan et al. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 61, 363–372 (2015); Y. Kayiteshonga et al. Rwanda Psychological Well being Survey 2018 (Govt of Rwanda, 2021).

Lengthy-term help for survivors is essential, as a result of many can grow to be retraumatized. For instance, media experiences about violence in close by elements of the Democratic Republic of the Congo can carry again recollections, says Iyamuremye. And yearly commemorations that final from April to July, referred to as kwibuka within the nationwide language, Kinyarwanda, carry challenges. “You will notice individuals who fall, who’re agitated, who cry” as a result of what they expertise triggers a reminiscence, says Iyamuremye.

For this 12 months’s commemorations, the RBC and different organizations have skilled 5,000 responders round Rwanda to help distressed individuals. However Iyamuremye and his colleagues have learnt that the commemorations themselves could be therapeutic: they offer individuals the chance to speak about their trauma and help one another.

And researchers have discovered that even individuals who weren’t alive throughout the genocide are struggling. “Intergenerational trauma is a problem and a actuality in Rwanda. This must be focused with sturdy, sturdy interventions,” says Iyamuremye.

Trauma throughout generations

On the Rwanda Navy Hospital on Kigali’s outskirts, Léon Mutesa, a doctor and, for a very long time, the nation’s solely geneticist, is seeing moms and infants at his paediatric clinic. Mutesa, who directs the Middle for Human Genetics on the College of Rwanda, was the primary to discover the results of Rwandans’ trauma on the genetic degree. As an undergraduate within the early 2000s, Mutesa noticed that youngsters born to ladies who had been pregnant in 1994 additionally exhibited indicators of trauma. Throughout commemorations, the kids expressed signs equivalent to PTSD, despair, anxiousness and hallucinations from an occasion that they hadn’t skilled.

Impressed by research of Holocaust survivors2, Mutesa devised a small research to research whether or not the trauma from the genocide had left epigenetic marks on people’ DNA by way of the addition of methyl teams to sure areas.

In that research3, carried out in 2012, Mutesa’s crew sampled blood from ladies who have been pregnant in 1994 and their youngsters, in addition to management individuals who weren’t uncovered to the genocide. The crew discovered proof that genocide survivors and their youngsters bore comparable epigenetic marks on sure sections of DNA.

Geneticist Léon Mutesa has studied DNA markings in genocide survivors and their youngsters.Credit score: AP Picture

Hoping to start out a bigger research, Mutesa collaborated with Stefan Jansen, a Belgian neuroscientist who had been on the College of Rwanda since 2011. In 2017, the pair, with US companions, gained funding from the US Nationwide Institutes of Well being to increase their investigations.

“We discovered that these moms who have been uncovered had round 24 differentially methylated areas, which is basically excessive in comparison with the management group,” says Clarisse Musanabaganwa, a medical analysis analyst on the RBC who was a part of Mutesa and Jansen’s crew. The crew discovered that lots of the methylated areas have been the identical in moms and within the youngsters that they have been pregnant with throughout the genocide4,5. The analysis signifies a manner through which trauma can transcend not less than one era, and the researchers recommend that lasting results may very well be handed down by way of a number of generations by way of a mechanism of epigenetic inheritance.

However the thought of multigenerational epigenetic inheritance is controversial. Many scientists are sceptical about whether or not methylation marks on DNA in people could be inherited.

“I’m not conscious of any actually convincing case the place the transgenerational inheritance — inheritance of methylation patterns — has been demonstrated,” says Timothy Bestor, a molecular biologist in Gaylordsville, Connecticut, who holds an emeritus place at Columbia College in New York Metropolis.

However Mutesa and Jansen are seeing some sensible advantages of their work. When the scientists mentioned with research individuals that their trauma might affect their youngsters, they noticed the individuals’ resilience enhance. As an illustration, if survivors’ youngsters have been performing poorly in class, mother and father now noticed a doable cause. The researchers might help youngsters with psychotherapy. “They may now perceive why that is taking place to their youngsters,” says Mutesa.

Organic research even have a broader significance, says Jansen. “We wish to proof that, and have that recorded for historical past: that is what occurred.” The proof helps to struggle genocide denial, he says.

Past the epigenetic analyses, Jansen and his colleagues have strengthened methodological approaches to learning neighborhood psychological well being in Rwanda. These research have knowledgeable analysis on conflicts elsewhere, equivalent to in Iraq, says Jansen.

Classes from Rwanda

The majority of the analysis on the genocide in Rwanda has been within the social sciences and humanities — learning matters from reconciliation, peacebuilding and justice to the position of ethnic designations in a society after battle. As an illustration, neighbouring Burundi, which skilled ethnic violence in a roughly decade-long civil battle that began in 1993, selected to acknowledge ethnicities, whereas the Rwandan authorities eradicated formal ethnic distinctions after the genocide. In a worldwide research6 that in contrast international locations that had taken both method after battle, people who selected to acknowledge ethnic teams scored higher on societal markers equivalent to peace, democracy and economics.

A few of the skulls of people that have been killed whereas searching for refuge at Ntarama in April 1994 are on show within the church.Credit score: Nichole Sobecki/VII/Redux/eyevine

The rising literature on genocides has revealed that they’ve enormous ramifications that reach effectively past the borders of the international locations the place they occur, say researchers.

“By way of the size of violence, the size of disruption, the size of struggling, they’re enormously essential occasions,” says Scott Straus, a political scientist on the College of California, Berkeley.

Research had been carried out nearly completely by Western students — though that’s beginning to change. Prior to now decade, as discussions of decolonizing analysis started in academia, Clark began working with the UK-based Aegis Belief, which runs the Kigali Genocide Memorial. An evaluation by Clark and his colleagues of 12 related journals confirmed that from 1994 to 2019, simply 3.3% of research on post-genocide Rwanda had been performed by students from the nation (see go.nature.com/3qapae7). In 2014, with funding from the Swedish and UK improvement companies, the Aegis Belief launched the Analysis, Coverage and Greater Schooling (RPHE) programme, an effort to ask Rwandan students to submit analysis proposals.

“There are cultural nuances that need to be informed by the very those that undergo these experiences,” says Sandra Shenge, who’s director of programmes on the Aegis Belief primarily based on the Kigali Genocide Memorial, and former RPHE supervisor. The grants have been modest — simply £2,500 (US$3,150) every. However the response to the programme was wonderful, says Shenge. The primary name acquired greater than 500 functions.

The goal was for Rwandan students to share their tales and for exterior researchers to supply help with recommendation on methodology, publishing and the way finest to disseminate outcomes. These research are collected in a useful resource referred to as the Genocide Analysis Hub.

“The RPHE was the very best factor that occurred to Rwandan researchers,” says Munyurangabo Benda, a thinker of faith on the Queen’s Basis, an ecumenical faculty in Birmingham, UK. “It’s the solely area the place Rwandan analysis has begun to have influence on coverage.”

Photographs of lives lower brief by the 1994 killings are on show on the Kigali Genocide Memorial.Credit score: Chris Jackson/Getty

Benda’s analysis7,8,supported by the RPHE, has already influenced coverage. His undertaking examined a state programme on reconciliation that had grown from a grassroots effort. His work exploring the guilt felt by youngsters of Hutu individuals was impressed by the expertise of his younger nephew in Denmark, whose father was a Hutu. In the future, his nephew’s class was learning the genocide in Rwanda and classmates requested him: “Have been your loved ones killers or survivors?” His nephew was traumatized.

The analysis helped to form programmes that the Rwandan authorities presents for college students of varied ages, says Benda.

The RPHE programme additionally holds classes for making the broader educational neighborhood extra inclusive. In keeping with Clark, “the issue is with journal editors and peer reviewers”, who typically dismiss work from Rwanda and different international locations due to preconceived concepts of high quality primarily based on the place the work has been produced.

A concept of genocides

One other creator whose work has been printed by way of the Genocide Analysis Hub is sociologist Assumpta Mugiraneza9. From a hilltop workplace with views over Kigali, Mugiraneza runs a company referred to as the IRIBA Centre for Multimedia Heritage. Iriba means ‘supply’ in Kinyarwanda, and the centre collects audio-visual archives of testimonies from the genocide and of life earlier than 1994.

Mugiraneza says she began this work to seize Rwanda’s heritage, which was in peril of disappearing. The nation’s historic oral traditions have been eroded by colonization, which imposed studying and writing. Consequently, Rwanda’s historical past is written with out this richer heritage, says Mugiraneza. “Let’s return to what we now have in widespread: sound and picture.”

Sociologist Assumpta Mugiraneza runs the IRIBA Centre for Multimedia Heritage.Credit score: Carl De Keyzer/Magnum Photographs

The centre, she says, is designed “to help the method of reappropriating the previous”. To consider genocide, “we should dare to hunt humanity the place humanity has been denied”.

IRIBA’s work is extraordinary, says Zoe Norridge, who research African literature and tradition at King’s School London. “That’s the type of work that may be performed by Rwandan students in depth in a manner that I feel outsiders by no means actually attain.”

Researchers agree that learning atrocities is a troublesome enterprise. “Analysis includes speaking to survivors who’ve endured unimaginable horror and placing your self within the place to pay attention and listen to and be empathetic,” says David Simon, who directs the Genocide Research Program at Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut.

Nonetheless, students say that, by way of these research, they’re growing a broader understanding by figuring out similarities amongst totally different genocides. These embrace what occurred in Rwanda and the Holocaust, in addition to within the genocide of the Armenian individuals in 1915 and of the Herero and Nama individuals in what’s now Namibia, beginning in 1904.

All of them shared widespread substances, in accordance with researchers. The primary is racializing members of society and figuring out an ‘inferior’ phase of the inhabitants to be eradicated. Different elements embrace planning organized massacres and spreading an ideology throughout a complete society. The final element is the involvement of the state and its establishments, equivalent to spiritual institutions and colleges, as individuals within the killings, says historian Vincent Duclert, who’s France’s main scholar on the 1994 genocide.

Research in Rwanda helped to solidify the idea, says Duclert. “This sample was actually bolstered by the genocide of the Tutsi.”

One other lesson from Rwanda, say researchers, is the necessity to search a number of narratives — from individuals inside and outdoors the area, and from perpetrators in addition to survivors. “In 1994, and within the years instantly after, there was a quite simple narrative in regards to the Rwandan genocide being pushed by historic tribal hatreds, and that it nearly defined itself away,” says Elisabeth King, who research peace, battle and training at New York College. Students, says King, have a vital half to play in growing nuanced accounts of the complicated political and social elements that underlie these occasions. These explanations, in flip, will help researchers and others to grasp why individuals commit atrocities, and will in the end contribute to growing approaches that assist to cease them.

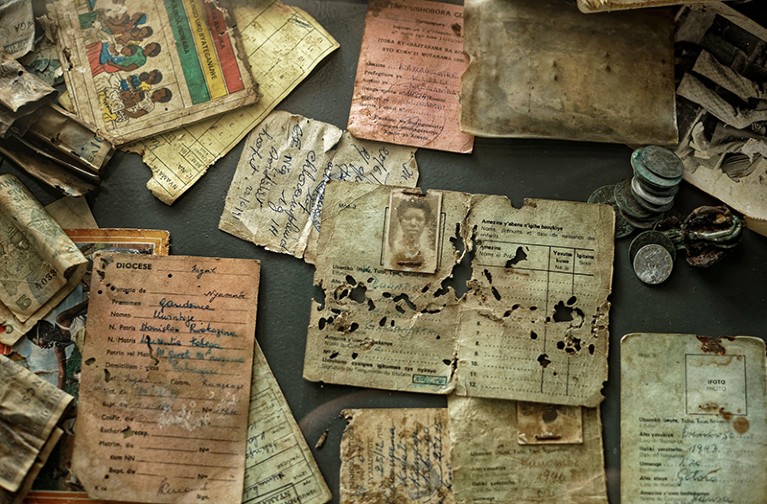

Belongings of individuals killed at Ntarama, together with identification playing cards, which confirmed individuals’s ethnicities.Credit score: Ben Curtis/AP Picture/Alamy

Straus can also be learning causal elements shared by totally different genocides, and why some conflicts which have the substances of genocide don’t escalate into them — violence in Mali within the Nineteen Nineties and Côte d’Ivoire within the early 2010s are two examples10.

Some students say that learning genocides can yield many advantages, however that stopping them from taking place is in the end a political matter determined by nations and worldwide our bodies.

Aggée Shyaka Mugabe, performing director of the Centre for Battle Administration on the College of Rwanda, is pessimistic in regards to the extent to which learning genocides can in the end cease them. “What we publish informs public insurance policies,” says Mugabe, who research transitional justice and peacebuilding11. However that doesn’t translate into one thing on a regular basis individuals can perceive, he provides.

Some have additionally raised considerations that it may be troublesome for Rwandan researchers to check matters associated to genocide freely, due to stress from the federal government to comply with a sure narrative on politically delicate points. However Mugabe rejects the concept analysis performed inside Rwanda isn’t helpful due to the perceived political stress. “A few of my papers have a essential side,” he says. “There isn’t any police attempting to inform me what to put in writing or what to not write.”

Survivors’ tales

One concern amongst students is that there was much less concentrate on elevating the voices of survivors, on condition that judicial inquiries centered a lot on perpetrators.

Jean Pierre Sagahutu is a kind of survivors. “I can’t let you know all the things that occurred in 1994 as a result of it’s too exhausting,” he says. “I bear in mind all the things as if it have been yesterday,” he says. “It’s as if I’m seeing it now.” Sagahutu survived by hiding in a septic tank for greater than two months. In that point, his father and mom have been killed. Initially skilled as an accountant, Sagahutu started driving taxis after the genocide and labored as a ‘fixer’ for individuals visiting the nation for tasks, typically interviewing génocidaires, the perpetrators of the violence towards the Tutsi. “Typically my ears harm, however it made me perceive what the individuals had actually performed. And in the long run, it grew to become remedy.”

In 2019, he met Duclert, whom French President Emmanuel Macron had commissioned to conduct a research on France’s position within the genocide, owing partially to the French authorities’s help of Rwanda’s pre-genocide Hutu authorities. In 2021, Duclert introduced his 1,000-page report12, which concluded that French authorities noticed proof of a coming genocide as early as 1990 however didn’t take sufficient measures to cease it.

Sagahutu takes positives from Duclert’s report, however says that students have extra work to do: “I’d like researchers to attempt to be taught, to essentially dig and discover out what the true causes of the genocide have been,” he says. “As a result of the genocide was not a recreation of probability, it was one thing that had been effectively ready for a very long time.”

One of the vital essential instruments for researchers is recording the testimony of survivors, says Yolande Mukagasana, who wrote the primary complete survivor’s account of the genocide, which was printed in French in 199713. Mukagasana, now 69, has remained a author and activist, and is decided to maintain the reminiscence of the genocide towards the Tutsi alive. As a part of her work, she has talked to survivors of different genocides and mass killings and he or she sees similarities in these occasions, no matter the place on the planet they occurred. “The ideology of hate is identical,” she says, including that survivors expertise “precisely the identical struggling”.

Yolande Mukagasana wrote the primary complete account of the genocide by a survivor.Credit score: Chris Schwagga

In 1994, Mukagasana was a nurse and a profitable Tutsi lady who ran her personal well being clinic. When the killings began, Mukagasana and her husband separated, hoping that their three youngsters could be safer with him. Throughout the months of the genocide, through which she was protected by Hutu individuals, she started writing her testimony on scraps equivalent to cigarette packets.

Mukagasana’s husband and kids have been killed. When she reached security on the Hôtel des Mille Collines — featured within the 2004 movie Lodge Rwanda — one of many first issues she wished was a pen and paper to report what had occurred.

At IRIBA, Mugiraneza is aware of the significance of documenting the occasions of 1994. However she additionally strives to gather proof of life earlier than. “The marriages. The love songs. The buildings, the proverbs, the tales — all these issues which are so magnificent however are seen as trivial.”

“Folks negotiate an area for pondering, for giving that means to life — which permits us to higher perceive what extermination and demise are.”

[ad_2]

Supply hyperlink