[ad_1]

A photographic archive has been found in Lyon, France, that provides treasured element to what we all know in regards to the founding of the world’s first police crime laboratory in 1910 and its creator, Edmond Locard, a pioneer of forensic science.

The massive assortment, which contains greater than 20,000 glass photographic plates that doc the laboratory’s pioneering scientific strategies, crime scenes and Locard’s private correspondence, is thrilling historians at a time when many take into account that forensic science has misplaced its manner. “There’s a motion to look again to the previous for steering as to the best way to renew the science of policing,” says Amos Frappa, a historian affiliated with the Sociological Analysis Centre on Regulation and Prison Establishments in Paris, who’s overseeing the evaluation of the pictures.

She was convicted of killing her 4 kids. May a gene mutation set her free?

Within the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many individuals in Europe and past have been excited about how criminals could be precisely recognized by utilizing strategies comparable to fingerprint, blood and skeletal evaluation. Locard was the primary individual to create the appearance of forensic science. He established the primary scientific lab that got here beneath the aegis of the police, and that was devoted to finding out ‘traces’ of prison exercise collected from crime scenes.

Storage discover

The gathering of photographic plates virtually didn’t survive. It languished for many years in a storage belonging to the Nationwide Forensic Police Division in Ecully, a Lyon suburb. In 2005, the glass plates have been rescued from the storage and saved in Lyon’s municipal archives. However on the time, the Lyon archives lacked the assets to deal with the gathering correctly, says director Louis Faivre d’Arcier. It wasn’t till 2017 that an inspection revealed that the plates’ gelatine layer containing the picture data was, in lots of circumstances, contaminated with mould. After a sorting and decontamination mission in 2022, conservators saved round two-thirds of the plates.

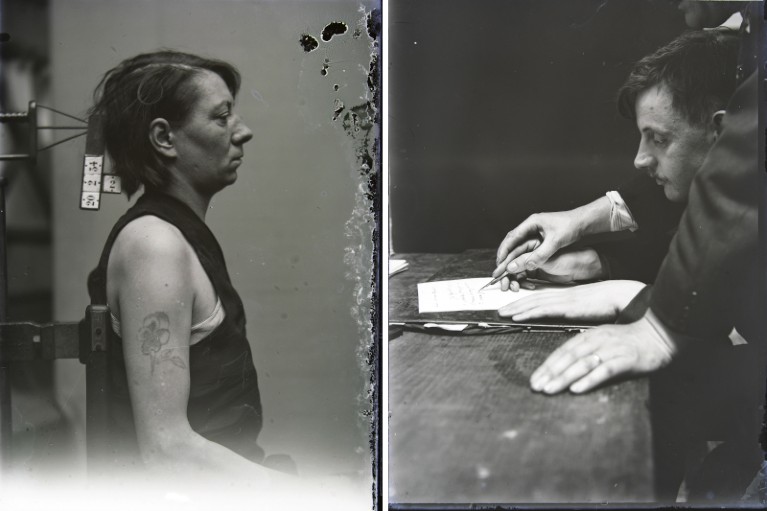

Left: A tattooed lady named Marie-Clémentine in 1934; Edmond Locard’s crew used tattoos as a manner of figuring out potential criminals. Proper: Handwriting evaluation as a method of identification was investigated however later spurned by Locard, who deemed it unreliable.Credit score: Archives municipales de Lyon

The mammoth job of digitizing the contents of the delicate plates, that are largely unindexed and disordered, grew to become doable solely when a neighborhood writer and historian of funerary practices, Nicolas Delestre, supplied to finance it. In collaboration with the municipal archives, his crew developed a photographic protocol to seize as a lot data from the plates as doable. The digitization shall be accomplished this spring, to coincide with the publication of Frappa’s French-language biography of Locard. The gradual rebuilding of the indexes continues.

Locard, who labored within the early to mid-twentieth century, is known for his maxim, which is normally formulated in English as “Each contact leaves a hint.” Educated as a forensic pathologist, he turned to the research of hint proof after a French political scandal referred to as the Dreyfus affair, through which a Jewish military officer referred to as Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of espionage. Through the affair, Locard’s mentor Alphonse Bertillon, who had invented a technique of figuring out folks by bodily measurements, was referred to as on as a handwriting specialist, regardless of having no experience within the area. He wrongly recognized Dreyfus because the writer of an incriminating be aware.

Forensic science: The soil sleuth

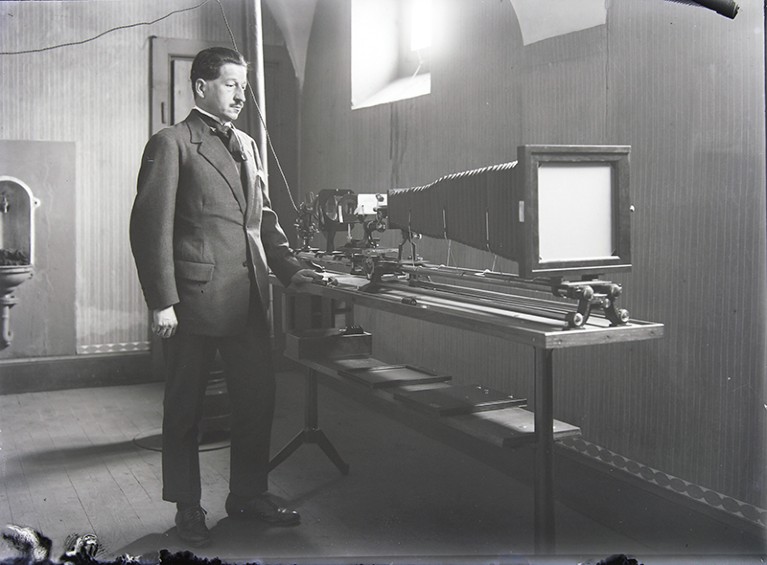

Locard, seeing different nations undertake fingerprint identification, embraced that technique as a substitute. In 1910, he arrange his laboratory within the attic of Lyon’s predominant courthouse, and steadily expanded his scientific analyses to incorporate traces comparable to blood, hair, mud and pollen.

Sherlock Holmes connection

This a lot was recognized from printed sources, however the photographic archive affords particulars in regards to the social and mental milieu that produced Locard, onthe scientific networks through which he was embedded, and on how his pondering developed as he experimented and made errors. His exchanges with contemporaries in nations together with Germany, Switzerland, Italy and the USA formed his strategy, which could be why he didn’t take into account himself a founding father of a brand new area. However Locard’s concepts — his scientific strategies and his insistence on meticulously finding out crime scenes — fell on fertile floor in Lyon’s police chiefs and judges, who, not like their Parisian counterparts, accepted the proof that such approaches generated. “Lyon was a receptacle,” says Frappa.

Edmond Locard utilizing a photographic bench within the Nineteen Twenties.Credit score: Archives municipales de Lyon

The brand new assortment reveals Locard’s crew at work. It captures their tools and experiments, and the forensic traces they analysed. The close-knit group socialized collectively, acquired worldwide guests and investigated myriad means by which individuals could possibly be recognized. A technique was to have a look at folks’s tattoos, and the gathering incorporates a big set of tattoo photographs. Locard took inspiration from many sources, together with the Lyon-based Lumière brothers, who have been pioneers of cinematography, and the creator of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, with whom he corresponded. In time, Locard discarded some strategies — notably, handwriting evaluation — deeming them unreliable.

Since 2009, when a report from the US Nationwide Analysis Council discovered that many trendy forensic strategies have been inadequately grounded in science, the self-discipline has struggled to reorient itself. “By the late twentieth century, it’s honest to say that forensic science had grow to be an adjunct of regulation enforcement with out allegiance to science,” says Simon Cole, who research criminology, regulation and society on the College of California, Irvine, and directs the US Nationwide Registry of Exonerations. Cole has written in regards to the issues with fingerprint identification, and final yr reported on the fallibility of microscopic hair comparability. These strategies are routinely used to analyze crimes in the USA and elsewhere, and the proof they generate is admissible in court docket.

Fashionable troubles

The 2009 report advised that bettering forensic science would require bigger labs through which various specialists have been insulated from one another and from the police to stop bias. The difficulty with that view, says Olivier Ribaux, director of the Faculty of Prison Sciences on the College of Lausanne in Switzerland, is that, when contemplating the doubtless infinite variety of traces {that a} crime scene can generate, some subjective choice by people is inevitable. To make sure that this choice is as informative and as unbiased as doable, the forensic scientist should perceive a hint in its context — as Locard’s maxim in French initially implied. “The issue with the massive labs is that they’ve severed the reference to the crime scene,” Ribaux says.

He favours an alternate mannequin through which smaller labs make use of generalists, who can oversee specialists in sure fields, comparable to ballistics and DNA, however may supply a extra holistic view of a case. These generalists would work carefully with the police — a return to Locard’s strategy, in different phrases. However the two aren’t mutually unique, Ribaux says. They’re simply snapshots of the continued debate about how the sphere ought to reinvent itself.

That debate will certainly be fuelled by the rising portrait of Locard, generally dubbed the French Sherlock Holmes, whom Frappa describes as “a person so visionary he predicted, appropriately, that he could be forgotten”.

[ad_2]

Supply hyperlink