[ad_1]

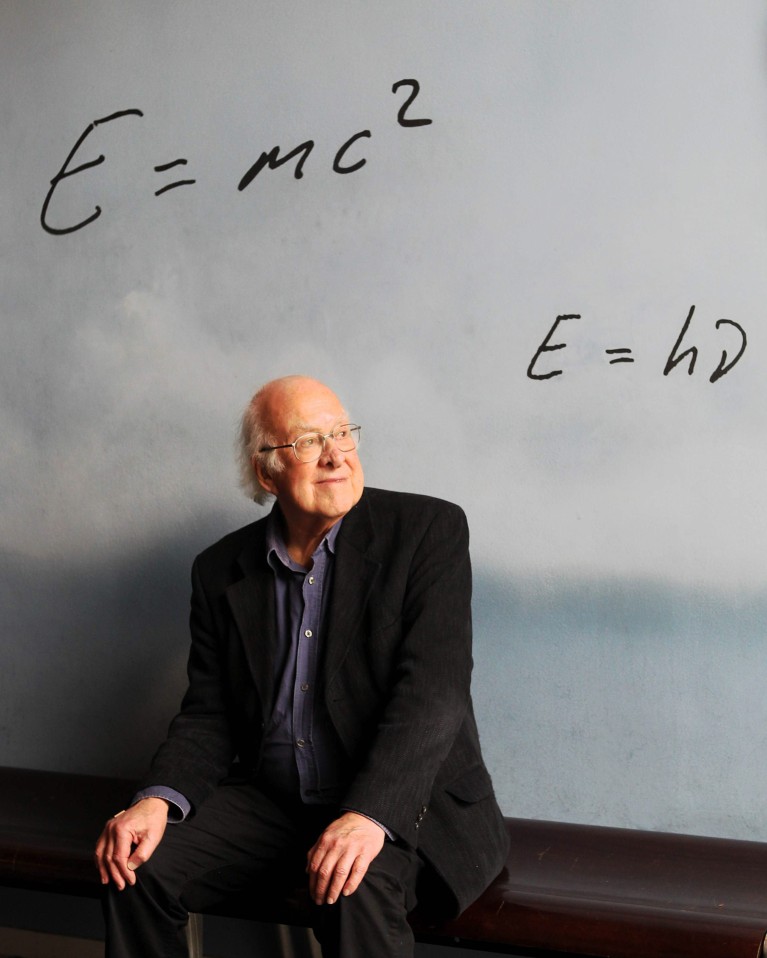

Credit score: Toni Albir/EPA/Shutterstock

Throughout just a few weeks in the summertime of 1964, Peter Higgs, a theoretical physicist on the College of Edinburgh, UK, wrote two brief papers outlining his concepts for a mechanism that would give mass to elementary particles, the constructing blocks of the Universe. His intention was to rescue a idea that was mathematically interesting however finally unrealistic as a result of the particles it described had no mass. The second paper drew consideration to a measurable consequence of his proposal — it predicted the existence of a brand new huge particle. Almost half a century later, the invention of the anticipated particle introduced Higgs, who has died aged 94, a share of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics.

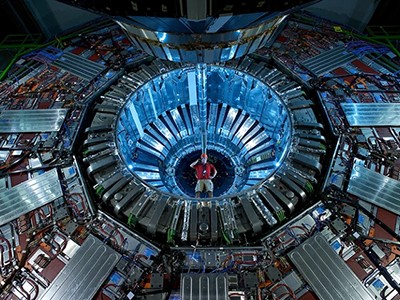

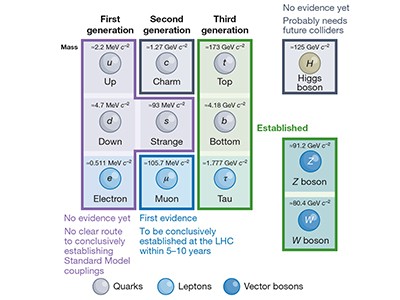

The mechanism Higgs described turned a key element of the usual mannequin of particle physics throughout the Seventies, however the related particle remained stubbornly elusive. Then, in 2012, two large experiments run by greater than 6,000 physicists at CERN, Europe’s high-energy physics laboratory close to Geneva, Switzerland, found one thing with the suitable properties. By then, the particle had achieved fame because the Higgs boson, though the self-effacing Higgs would normally seek advice from it as ‘the scalar boson’ in reference to its key attribute of getting no intrinsic spin.

The ‘brazen’ science that paved the best way for the Higgs boson (and much more)

Higgs was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1929, however his father’s work as a sound engineer for the BBC took the household to Bristol, the place Higgs attended Cotham Grammar College. There, he noticed a number of mentions on the honours boards of a earlier pupil, Paul Dirac, who had earned a share of the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in quantum mechanics. Impressed, Higgs took up physics at King’s School London, the place he obtained a PhD in 1954.

As a hitch-hiking scholar, Higgs had found a liking for Edinburgh, so in 1960 he was comfortable to be appointed as a lecturer there. He picked up on a long-standing curiosity in symmetry in subatomic particle physics, impressed specifically by the work of the longer term Nobel prizewinner Yoichiro Nambu, a Japanese American physicist then on the College of Chicago in Illinois. In physics, symmetry is linked to the conservation of portions comparable to vitality, momentum and electrical cost. Engaged on a idea that had an underlying symmetry however wherein particles had no mass, Nambu was trying to generate mass by way of a mechanism often known as spontaneous symmetry breaking. Nonetheless, such symmetry breaking would additionally produce massless particles with zero spin, for which there was no proof.

Peter Higgs: the person behind the God particle

This appeared a lifeless finish, however in 1964, Higgs realized that it was doable to get spherical the issue utilizing gauge idea, which has the type of symmetry discovered, for instance, within the established idea of electromagnetism. Higgs confirmed that the massless particles related to spontaneous symmetry breaking change into ‘absorbed’ into huge particles. He printed two brief papers on this theme1,2, the second of which explicitly predicted a large spin-zero particle. It fell to different physicists to appreciate that this mechanism for spontaneous symmetry breaking was key to a mathematically coherent gauge idea of particle physics that unites the electromagnetic interactions between particles with the weak interactions concerned in sure types of radioactivity. This Nobel-prizewinning ‘electro-weak idea’ turned one of many twin pillars of the usual mannequin of particle physics, and was properly established by experiments by the Nineteen Nineties.

The sphere had appeared one thing of a scientific backwater within the Nineteen Sixties, however Higgs was not working alone. Two different papers have been printed in 1964 on the mechanism3,4, one showing simply earlier than his personal. However solely Higgs drew consideration to the related huge spin‑zero particle, which within the Seventies started to be referred to as the Higgs boson. The catchy title caught.

Round this time, after his marriage broke down, Higgs discovered he was shedding his manner in theoretical particle physics. Along with educating, he turned concerned within the union aspect of college life and wrote few physics papers. However, as appreciation of his work on spontaneous symmetry breaking grew, he was more and more requested to offer talks, a preferred title being ‘My life as a boson’. He retired in 1996.

The Higgs boson turns ten

The award of the Nobel prize to Higgs and Belgian physicist François Englert — the surviving writer of the paper printed simply earlier than Higgs’s in 1964 — got here as little shock to anybody, together with Higgs, as a result of it had been mooted for the reason that Nineteen Eighties. Nonetheless, curiosity within the Higgs boson had elevated over time, not solely amongst particle physicists but additionally among the many common public and the media. It reached fever pitch after the development of CERN’s Giant Hadron Collider, which was billed by many because the machine that will uncover the final lacking piece of the usual mannequin. This intense curiosity introduced fame at a degree nobody might have imagined within the Nineteen Sixties, and the quiet physicist turned a media star, earlier than retiring for a second time when he reached 85.

A eager music lover, Higgs had little curiosity within the trappings of recent know-how — he famously had no tv and didn’t use the Web. But he was removed from being distant from the world. He had a powerful social conscience and was a member of the Marketing campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and Greenpeace at varied occasions. Humble in lots of respects, with an infectious sense of humour, he was pleased with the work that he had at all times identified was vital and which finally introduced him fame.

Competing Pursuits

The writer declares no competing pursuits.

[ad_2]

Supply hyperlink